Model soil stack vent and pipe

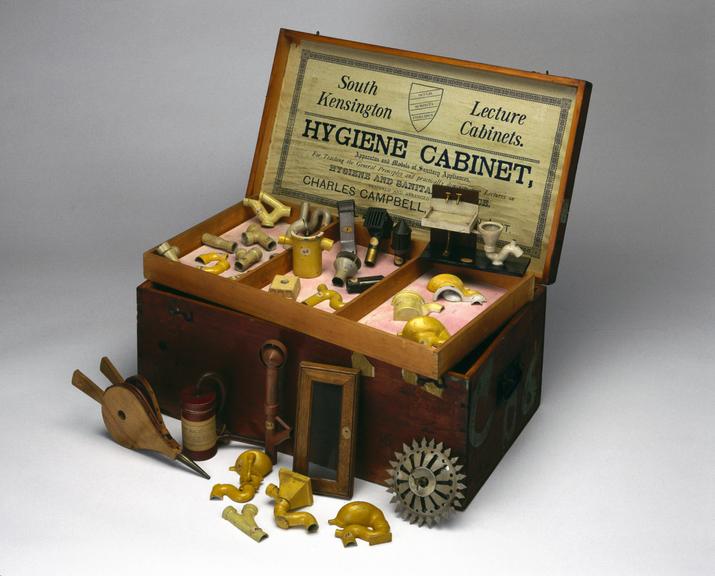

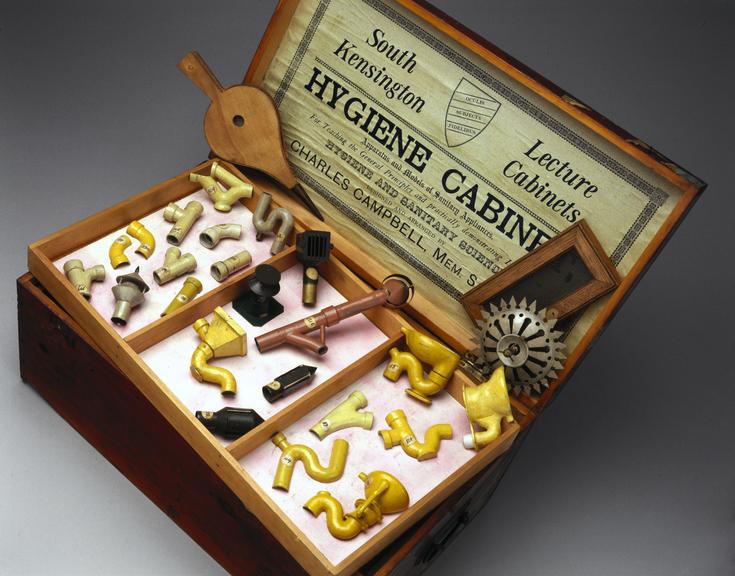

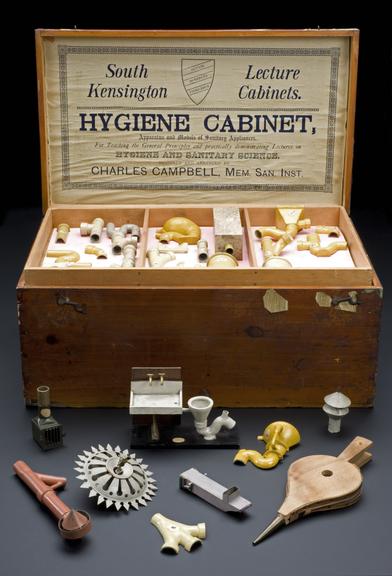

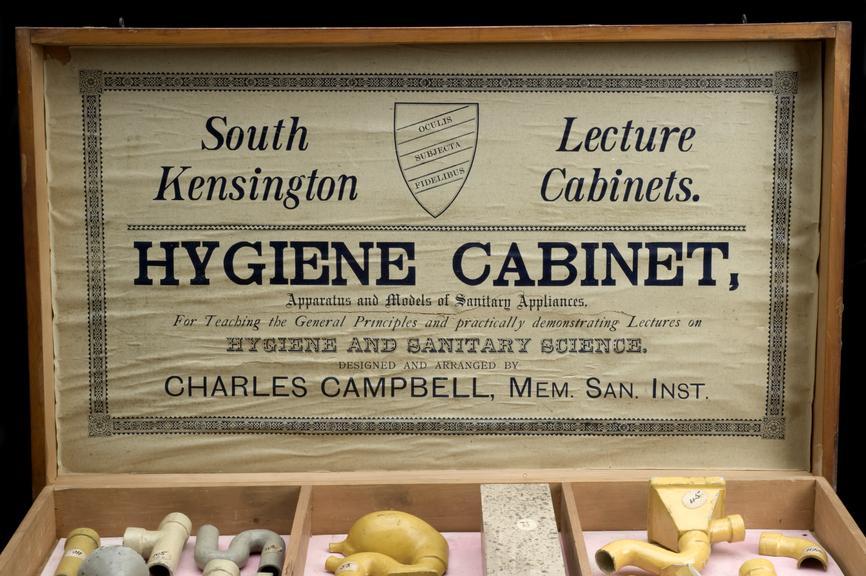

Maroon painted metal model of a soil stack vent and pipe, with sticker marked with the number 121E. Such devices were intended to prevent the back flow of smells from the mains sewer coming into the home – it was sometimes known as the ‘stench pipe’. One of many models contained in a lidded wooden ‘Hygiene Cabinet’, one of a possible series of so-called ‘South Kensington Lecture Cabinets’, to be used for instruction and demonstration in the general principles of hygiene and sanitary science, designed by Charles Campbell, a member of the Sanitary Institute, London, c.1895.

Charles Campbell, a member of the Sanitary Institute, designed and arranged the cabinet which contained this model and many others. It was used for lectures on hygiene and sanitary science – but in the 1890s who is attending such talks? Sanitary Inspectors employed to check and report on the state of hygiene in their neighbourhood are the most likely audience. It was an essential part of their training, in preparation for examinations held by the Sanitary Institute, London, and other public health associations.

Women gained the sanitary officer’s certificate as often as men. In the mid-1890s, Hilda Martindale, influential author, civil servant and prominent campaigner for the improvement of working conditions, attended lectures at the Sanitary Institute. On passing the examination, she went on to study public health and hygiene at Bedford College, London. She later worked as a factory inspector for more than thirty years, becoming Deputy Chief Inspector in 1925.

It’s possible Hilda Martindale was taught using either the cabinet this model is kept in, or one that was very similar, which has three layers of miniature water supply and sewerage fittings, sanitary appliances such as toilets and wash basins, and equipment relating to the ventilation of buildings. Best practice could be demonstrated, but the cabinet also contains items showing incorrect or defective fittings posing a hazard to health.

Similar exhibits were held by the Parkes Museum, founded in 1876 as a memorial to military hygiene reformer Edmund Alexander Parkes. It too aimed to educate and inform the general householder and building tradespeople, complementing the work of the Sanitary Institute (with which it merged in 1888) to raise standards of public health.

- Measurements:

-

.136 kg

- Materials:

- steel (metal) , paint and paper (fibre product)

- Object Number:

- 1895-50 Pt1

- type:

- hygiene model and sanitary appliances