Apollo 10 Command Module, Call Sign 'Charlie Brown'

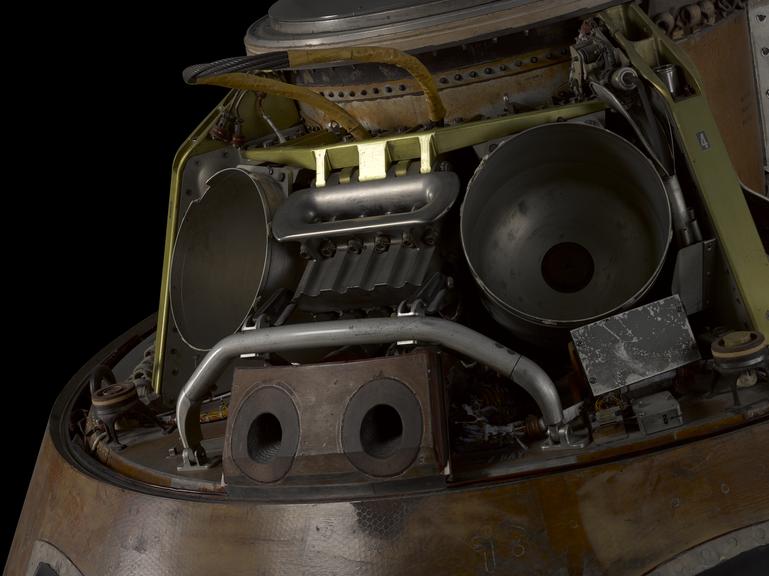

Apollo 10 command module, call sign 'Charlie Brown', by North American Rockwell Corporation, Downey, California, United States, 1969. Apollo 10, carrying astronauts Thomas Stafford, John Young and Eugene Cernan, was launched in May 1969 on a lunar orbital mission as the dress rehearsal for the actual Apollo 11 landing. Stafford and Cernan descended in the Lunar Module to within 14 kilometres of the surface of the Moon, the closest approach until Neil Armstrong and Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin in Apollo 11 landed on the surface two months later.

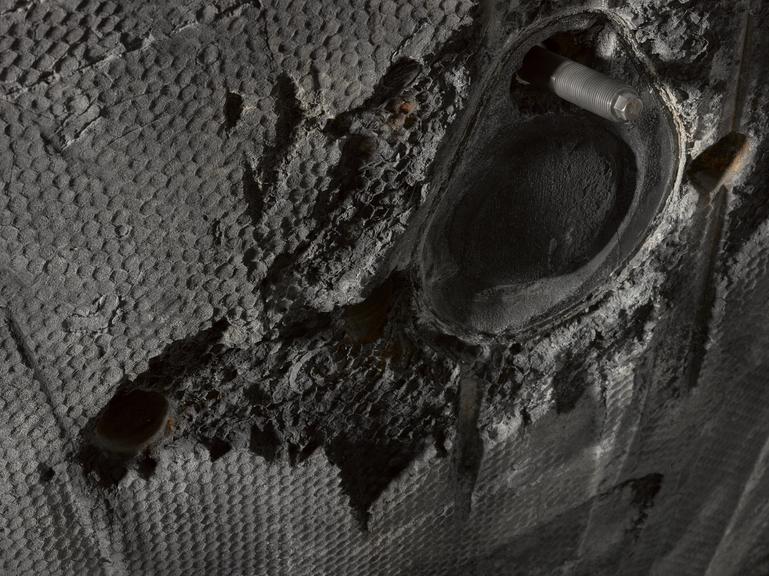

The command module was the only part of the Apollo spacecraft to return to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean where the spacecraft and astronauts were recovered by helicopter and aircraft carrier.

Charlie Brown is on loan from the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution.

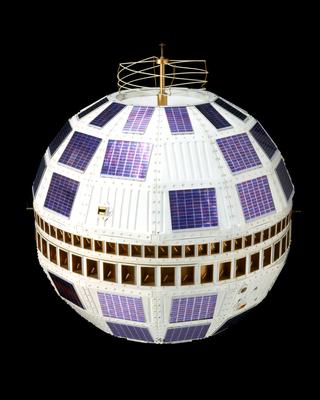

In May 1961, when President Kennedy proposed a moon landing 'before this decade is out', he was committing the United States to a supreme focus for technological effort. The programme also reflected the Cold War competition between Soviet and American ideologies and defence fears in America that it might be losing the 'missile race' following the Soviet launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in 1957.

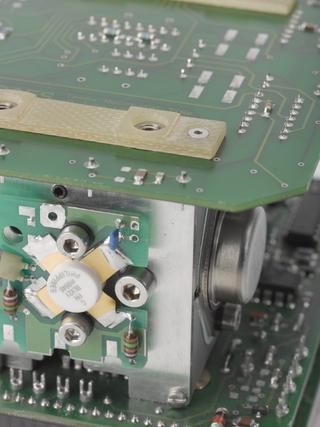

Although the Apollo programme had its roots in this fearful Cold War climate the Moon landing remains an extraordinary achievement at the limit of what was possible. For example, the missions used, in aggregate, the largest amount of computing power ever assembled at this time, to control the navigation and rendezvous problems of the craft. It also represented a huge industrial effort which engaged 390,000 people and took five per cent of the US Federal budget in 1965. The project generated enormous passion. North American Aviation, the contractors for the capsule, estimated that some 20 per cent of the 500 million man-hours in the project were contributed as free overtime by staff.

In this capsule Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan travelled around the Moon in 1969 as a dress rehearsal for the Apollo 11 landing which followed in July.

Many 'spin-offs' have been claimed for the Apollo flights, including the minaturisation of computers, Teflon and a huge boost to US technology. However, its most portent and enduring legacy perhaps lies in the views of Earth that the astronauts captured. These 'Earthrise' photographs resonated with a developing environmental consciousness and helped awaken us to the fragility of our planet.

Details

- Category:

- Space Technology

- Object Number:

- 1976-106

- Materials:

- aluminium alloy, stainless steel, metal (unknown) and epoxy-resin

- Measurements:

-

overall: 4000 x 4000 mm (approximate)

- type:

- manned spacecraft

- copyright:

- National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

- credit:

- Lent by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Washington, DC